Winning the Innovation Game With Jobs-to-Be-Done Theory

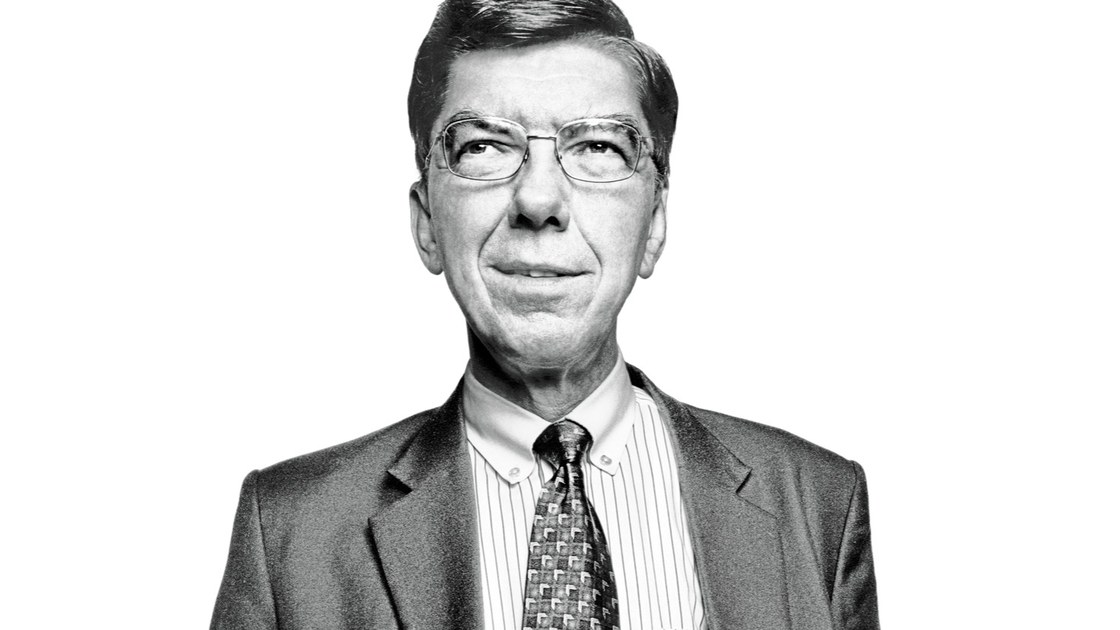

Each year, 30,000 new consumer products are launched, and 95% of them fail. According to Harvard Business School professor, Clayton Christensen, most companies struggle to market revolutionary offerings because they misunderstand customers’ demands. With his “Jobs-to-Be-Done” theory, Christensen shows how seeing innovation through a new lens can help understand customer behavior better and boost business growth.

While most corporate leaders understand the importance of innovation for growth strategies, many fall short when it comes to execution.

A recent McKinsey poll revealed that 84% of global executives considered innovation as critical, but that 94% were dissatisfied with their innovation performance.

These results may seem shocking, considering that companies know more about their customers than ever before. With current technologies, organizations can collect a substantial volume of customer information and perform in-depth analyses to tailor their offers accordingly.

Despite sophisticated, precise marketing processes, many leading companies fail to catch the next wave of innovation in their industries.

What makes innovation so challenging?

The why behind the what

The purpose of innovation is to create products and services that address unmet consumer needs, but most organizations struggle to predict and define these requirements with precision.

Although companies can collect more customer data than ever before, they do not have access to information against which they can evaluate their ideas for new products. Most businesses have yet had to develop skills and strategies to gain deep insight into customer needs.

Harvard professor Clayton Christensen, regarded as one of the world’s top experts on innovation and growth, believes that businesses often fail at innovation because they focus too much on finding correlations between their products and customer data.

When planning new products, marketing and development teams tend to segment their consumer base and position their merchandise accordingly. They usually divide the market into product categories, such as price or function, or separate their customers into target demographics like gender, age, education, or income level.

While this approach allows companies to identify patterns in customer behavior quickly, it does not assist to a better understanding of what causes people to buy their offerings.

Customers rarely plan their shopping by conforming to specific segments. They take life as it comes, and seek new products or services when they need to complete tasks and activities, resolve problems, avoid certain situations, or achieve goals.

Christensen thinks that executives should try to understand what the customer wants to accomplish when using a product or a service. In other words the unit of analysis should be shifted away from products and customers towards the value the product is bringing to customers.

He makes the case that to understand what motivates people to act, we first must identify what exactly they need to do.

Professor Christensen first articulated this theory in a 2005 paper for the Harvard Business Review about marketing paradigms.

“When people find themselves needing to get a job done, they essentially hire products to do that job for them,” he wrote. “If a marketer can understand the job, design a product and associated experiences in purchase and use to do that job, and deliver it in a way that reinforces its intended use, then when customers find themselves needing to get that job done, they will hire that product.”

Christensen ’s approach has become known as the Jobs-to-Be-Done (JTBD) theory. As its name suggests, the concept is based on the notion that people buy products and services to “get a job done.” By understanding what that “job” is, businesses can create solutions that will win the marketplace.

Defining markets

The “job” statement embodies what customers are ultimately trying to achieve. Businesses can put the theory to practice by defining the customer and the job as a market. For example, dentists who are trying to repair a torn cheek retractor constitute a market.

By identifying markets this way, a company can clarify its target customers and create proper offerings the customer will want to purchase to accomplish a specific functional job. In his book Competing Against Luck, Christensen further states that we are willing to pay premium prices for a product that "nails the job" because "the full cost of a product that fails to do the job—wasted time, frustration, spending money on poor situations, and so on—is significant to us."

The theory is now widely known in corporative environments as a series of principles that explain how to make marketing more effective, understand customer behavior better, and accelerate the innovation process by focusing on the customer’s desired outcomes.

Before the JTBD theory, several marketing strategists evoked the idea of paying particular attention to what the customer is trying to achieve, but Christensen was the first to introduce it as a framework.

In his MBA course, Christensen illustrates the Jobs-to-Be-Done concept by giving an example from a well-known fast-food chain.

Hiring milkshakes

Several years ago, as the idea of Jobs-to-Be-Done was emerging, McDonald’s aimed to increase their milkshake sales.

The company started by segmenting its market by product and by demographics to create the profile of a typical milkshake drinker. The marketing department then asked people who fit the demographic to list the characteristics of an ideal milkshake.

Image credit: McDonald's

Customers provided clear guidance, and the company responded to that feedback by improving the milkshake. However, sales and profits did not grow.

McDonald’s then requested the help of one of Christensen’s fellow researchers, who approached the situation by deducing what “job” customers hired a milkshake to do. After spending several days in the chain’s restaurants to observe and document milkshake sales, he discovered that nearly half of the drinks were purchased before 8:30 in the morning by commuters who ordered them to go.

Christensen and his colleague stood outside a restaurant one morning to interview people who left with a milkshake in hand, asking them what job they had hired their drink to do.

Having never framed the question that way before, customers struggled to answer. However, as Christensen and his partner put the responses together, they realized that most of them bought the drink to do a similar job.

“They faced a long, boring commute and needed something to keep that extra hand busy and make the commute more interesting,” Christensen explains. “They weren't yet hungry but knew that they'd be hungry by 10 a.m. They wanted to consume something now that would stave off hunger until noon.”

Workers hired milkshakes instead of a bagel or a muffin because it was tidy while still appetite-quenching. Trying to drink a thick liquid through a straw also gave them something to do during their tedious commute.

Understanding the job to be done, McDonald’s could then respond by creating a morning milkshake that was thicker and contained more complex ingredients, breakfast-type ingredients.

For several customers, these drinks also served as a special treat for children. The company could respond to that job by creating a different, thinner milkshake that kids could quickly work through a straw.

Nailing a specific “job to be done”

Several leading companies have succeeded using the Jobs-to-Be-Done mechanism.

Hershey’s achieved breakout success when it created Reese’s Minis. Investigating the reasons why the sales of the original Reese’s were dropping, the company acknowledged that the format was too big and too messy and that the individual wrapping was inconvenient in multiple situations.

The accumulation of the cups’ wrappers would also induce guilt and make customers limit their consumption.

Hershey’s focused on the job that a new version of the product needed to do and created Reese’s Minis, which have no wrappers to leave traces of consumption, and come in resealable bags that customers can easily dip a hand into while on the go.

Image credit: Scrummy

Focusing on what customers seek to accomplish allows organizations to differentiate their offerings in ways that competitors are often unable to reproduce. IKEA, for example, is renowned for helping its customers do the job of furnishing a house or apartment right away. No company has yet managed to copy the Swedish furniture giant’s concept.

Professor Christensen claims that Procter & Gamble’s products success rate rose significantly when the brand started segmenting its markets according to a product’s job.

Procter & Gamble’s Crest brand, usurped by Colgate in the late 1990s, has regained the lead in many markets by making teeth whitening at home simple and affordable. As they respond to a specific need, innovative products like Crest Whitestrips and Crest 3D White toothpaste appeal to the company’s current customers while attracting new ones.

Jobs-to-Be-Done in the software industry

Christensen’s approach has proven beneficial for organizations across many different industries in recent years. While most of the writing on Jobs-to-Be-Done caters to creating physical products, the framework can also significantly help software companies.

It’s even easier for software companies to miss targets than with physical products. While no one aims to build bloated software, decisions from product managers, engineers, or founders can quickly bump the development of a simple tool off the rails.

The JTBD concept helps software companies focus on creating functionalities that customers genuinely want. By developing solutions that respond to existing demands, businesses do not have to bother convincing people that they need their products.

Intercom, which develops software to help companies stay in touch with customers via multiple channels, was one of the first organizations in the industry to adopt a JTBD perspective.

In their recent book Intercom on Jobs-to-Be-Done, co-founder and Chief Strategy Officer Des Traynor and his colleagues share some of the most valuable lessons they have learned from applying Christensen’s theory to their work.

Image credit: Intercom.com

Image credit: Intercom.com

When Intercom was still an early-stage start-up, executives were searching for direction. While the company was aware of the value of their features, Intercom didn’t know exactly who was using their products or for what reasons.

JTBD has allowed the team to identify and understand better the needs of their customers and how to improve their experience.

Focusing on motivations and outcome

Most software companies use buyer personas to create realistic representations of their target audience and tailor their offers accordingly.

Traynor explains that, while personas will always have their place in the development of a new product, making decisions based on attributes and personality traits might not be the best way to build great software. “That’s because products don’t match people; they match problems,” he writes.

The Intercom team has learned that what customers want to accomplish is much more important than the customers themselves. Traynor considers that software developers should focus on the job and the context of customers and create products well-tailored to what these people are already trying to achieve.

Personas ensure that members of development teams share the same vision of target users. These representations work well when the customer base is divided into different types of users with different needs, but it is not always the case when building software products.

“Some products are better defined by the job they do than the customers they serve,” Traynor explains. “For some products, customers come in all shapes and sizes, from all countries, all backgrounds, all salaries, and all levels of computer skills. The only thing in common is the job they need to get done.”

In such cases, getting a clear understanding of the job itself and what creates demand for it represents the best way to create a useful product.

For example, millions of people of all ages, with diverse attributes, use Facebook to share funny photographs and make their friends laugh.

“You may well be a talented photographer with more cameras than a Las Vegas casino. But when you hire Facebook, quality isn’t your concern. People are.”

People posting photos on Facebook or Instagram may have completely different characteristics and personality traits, but they all “hire” the social platform to do the job of instant sharing so their friends can see and react to what is happening.

While personas observe attributes and roles, Jobs-to-Be-Done looks at situations and objectives.

Personas may give an idea of who people are and what they do, but they never explain exactly why people do something. Focusing on characteristics rather than motivations and outcome can significantly limit a product’s audience.

To ensure they build valuable products, Intercom’s designers always use this sentence: “ [ When _____ ] [ I want to _____ ] [so I can _____ ].”

Image credit: Intercom

“When” refers to the situation, “I want to___” focuses on the motivation, and “so I can____” outlines the outcome.

This process helps employees understand and capture the problem in a concise format, making it actionable for the engineering team.

Identifying competitors

By providing the situational context that motivates people to use products, Jobs-to-Be-Done helps companies identify their real competitors.

Software builders tend to think that competition only exists in the same tool category. According to Traynor, they should completely ignore product categories and instead ask themselves who else is fighting for the same job to be done.

Focusing on the specific purpose of a product allows organizations to see all potential competitors. For example, video conferencing providers and airline companies can compete on the same outcome, as they can both be hired for business meetings.

Focus on improvement for the right reasons

Traynor explains that software developers should also keep in mind that customers adapt products to their needs and use them in creative ways.

When trying to improve products, companies have to make sure they understand exactly how their customers use it so it can perform that specific job even better.

Shortly after launching Intercom, the team added a map feature that allowed users to see where their clients were around the world. The tool became popular quickly, but Intercom could not work out exactly why customers were using it that much.

Traynor and his colleagues initially thought that their customers used the map to work out where they had the most clients, or see how many users they had in a given country. However, they realized that most people employed the tool to show it off to investors and on social media.

If they had tried to improve the map before they knew how people used it, Intercom’s designers would have focused on cartographical improvements, such as better geographical accuracy and clustering.

“All of those ‘improvements’ would have taken us months and would have resulted in a worse product, ” Traynor claims. “The customer wasn’t buying what we thought we were selling. It’s not a map. It’s a showpiece.”

The team focused on creating a beautiful animated map that users could share easily.

Focusing purely on how a product helps users, regardless of the category it fits in, allows developers to satisfy their target consumer base and ensures efficient innovation.

Successful innovation

With technological shifts and constant evolution of the marketplace, companies can quickly find themselves getting better and better at offering products and services that people want less and less.

By focusing on innovating their business model rather than their products, organizations can retain customers and ensure progress. The key to winning the innovation game lies in understanding what causes customers to make choices that help them accomplish specific goals.

While the application of the Jobs-to-Be-Done theory is still pretty new in the software industry, Intercom’s experience shows that this approach can help tech companies build valuable, user-centered products.

With a twist towards the software industry, Intercom has revived Clayton Christensen’s Jobs-to-Be-Done theory in the form of an incredibly digestible publication. Click here for a free PDF version. For other practical insights, check out Bob Moestra and Chris Spiek's site jobstobedone.org.